The History of Ancient Sumeria

Part 1 | -->

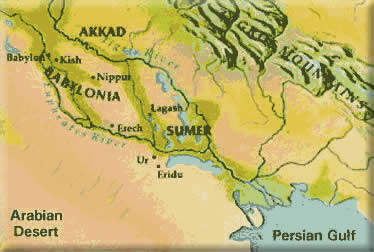

WHERE WAS MESOPOTAMIA?

Mesopotamia was approximately 300 miles long and 150 miles wide. It was located between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. These rivers flow into the Persian Gulf. The word Mesopotamia means "The land between the rivers". It was located in modern day Iraq.

The term "Sumerian" is an exonym (a name given by another group of people), first applied by the Akkadians. The Sumerians described themselves as "the black-headed people" (sag-gi-ga) and called their land ki-en-gir, "place of the civilized lords". The Akkadian word Shumer possibly represents this name in dialect.

The Sumerians, with a language, culture, and, perhaps, appearance different from their Semitic neighbors and successors were at one time believed to have been invaders, but the archaeological record shows cultural continuity from the time of the early Ubaid period (5200-4500 BC C-14, 6090-5429 calBC) settlements in southern Mesopotamia.

The challenge for any population attempting to dwell in Iraq's arid southern floodplain was to master the Tigris and Euphrates river waters for year-round agriculture and drinking water. In fact, the Sumerian language is replete with terms for canals, dikes, and reservoirs, indicating that Sumerian speakers were farmers who moved down from the north after perfecting irrigation agriculture there.

The Ubaid pottery of southern Mesopotamia has been connected via 'Choga Mami Transitional' ware to the pottery of the Samarra period culture (5700-4900 BC C-14, 6640-5816 calBC) in the north, who were the first to practice a primitive form of irrigation agriculture along the middle Tigris river and its tributaries.

The connection is most clearly seen at Tell Awayli (Oueilli/Oueili) near Larsa, excavated by the French in the 1980s, where 8 levels yielded pre-Ubaid pottery with affinities to Samarran ware.

Sumerian speakers spread down into southern Mesopotamia because they had developed a social organization and a technology that enabled them, through their control of the water, to survive and prosper in a difficult environment where, other than a possible indigenous hunter-gatherer population in the marshlands at the head of the Arabo-Persian Gulf and seasonal pastoralists, they had no competition.

A distinctive style of painted pottery spread throughout Mesopotamia in the Ubaid period, when the ancient Sumerian cult-center of Eridu was gradually surpassed in size by the nearby city of Uruk. The archaeological transition from the Ubaid period to the Uruk period is marked by a gradual shift from painted pottery domestically-produced on a slow wheel, to a great variety of unpainted pottery mass-produced by specialists on a fast wheel.

The date of this transition, from Ubaid 4 to Early Uruk, is in dispute, but calibrated radiocarbon dates from Tell Awayli would place it as early as 4500 BC.By the time of the Uruk period (4500-3100 BC calibrated), the volume of trade goods being inexpensively transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large temple-centered cities where centralized administrations could afford to employ specialized workers. It is fairly certain that it was during the Uruk period that Sumerian cities began to make use of slave labor, and there is ample evidence for captured slaves as workers in the earliest texts.

Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area - from the Mediterranean sea in the west, to the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, and as far east as Central Iran.

The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists, had a stimulating and influential effect on surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies.

The cities of Sumer could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies purely by military force; the domestic horse did not appear in Sumer until the Ur III period - one thousand years after the Uruk period ended. The end of the Uruk period coincided with a dry period from 3200-2900 BC that marked the end of a long wetter, warmer climate period from ca. 9,000 to 5,000 years B.P. called the Holocene climatic optimum.

When the historical record opens, the Sumerians seem to be limited to southern Mesopotamia, although very early rulers such as Lugal-Anne-Mundu are indeed recorded as expanding to neighboring areas as far as the Mediterranean, Taurus and Zagros, and not long after legendary figures like Enmerkar and Gilgamesh, who are associated in mythology with the historical transfer of culture from Eridu to Uruk, were supposed to have reigned.

The term 'Sumerian' applies to speakers of the Sumerian language. The Sumerian language is generally regarded as a language isolate in linguistics because it belongs to no known language family; Akkadian belongs to the Afro-Asiatic languages.

History

In the earliest known period Sumer was divided into several independent city-states, whose limits were defined by canals and boundary stones. Each was centered on a temple dedicated to the patron god or goddess of the city and ruled over by a priest or king, who was intimately tied to the city's religious rites.Some of the major cities included Eridu, Kish, Lagash, Uruk, Ur, and Nippur. As these cities developed, they sought to assert primacy over each other, falling into a millennium of almost incessant warfare over water rights, trade routes, and tribute from nomadic tribes.

The Sumerian king list contains a traditional list of the early dynasties, much of it probably mythical. The first name on the list whose existence is authenticated through archaeological evidence, is that of Enmebaragesi of Kish, whose name is also mentioned in the Gilgamesh epics. This has led some to suggest that Gilgamesh really was a historical king of Uruk.

The Sumerian king list is an ancient text in the Sumerian language listing kings of Sumer from Sumerian and foreign dynasties. The later Babylonian king list and Assyrian king list were similar. There are also slight similarities between the antediluvian portion of the list and the two sets of Genealogies of Adam in the Torah.

The list records the location of the "official" kingship and the rulers, with the lengths of their rule. The kingship was believed to be handed down by the gods, and could be passed from one city to another by military conquest. The list mentions only one female ruler: Kug-Baba, the tavern-keeper, who alone accounts for the third dynasty of Kish.

The list peculiarly blends from ante-diluvian, probably mythological kings with exceptionally long reigns, into more plausibly historical dynasties. It cannot be ruled out that most of the earliest names in the list correspond to historical rulers who later became legendary figures.The first name on the list whose existence has been authenticated through recent archaeological discoveries, is that of Enmebaragesi of Kish, whose name is also mentioned in the Gilgamesh epics. This has led some to suggest that Gilgamesh himself was a historical king of Uruk, and not just a legendary one. Conversely, Dumuzi is one of the spellings of the name of the god of nature, Tammuz, whose most present epithet was the shepherd.

Conspicuously absent from this list are the priest-rulers of Lagash, who are known directly from inscriptions from ca. the 25th century BC. Another early ruler in the list who is clearly historical is Lugal-Zage-Si of Uruk of the 23rd century BC, who conquered Lagash, and who was in turn conquered by Sargon of Akkad.

The list is central, for lack of a more accurate source, to the chronology of the 3rd millennium BC. However, the presence in the list of dynasties which plausibly reigned simultaneously, but in different cities, makes it impossible to trust the addition of the figures to produce a strict chronology. Taking this into account, many regnal dates have been revised in recent years, and are generally placed much later nowadays than the regnal dates given in older publications, sometimes by an entire millennium.

Some have proposed re-reading the units given in more realistic numbers, such as taking the figures, given in sars (units of 3600) for the antediluvians, as instead being either decades or simply years. Uncertainty, especially as to the duration of the Gutian period, also makes dates for events predating the Third dynasty of Ur (ca. 21st century BC) with any accuracy practically impossible (see also Shulgi, Ur-Nammu).

Some of the earliest known inscriptions containing the list date from the early 3rd millennium BC; for example, the Weld-Blundell Prism is dated to 2170 BC.

The later Babylonian and Assyrian king lists that were based on it still preserved the earliest portions of the list well into the 3rd century BC, when Berossus popularised the list in the Hellenic world.

Over the large period of time involved, the names inevitably became corrupted, and Berossus' Greek version of the list, ironically one of the earliest to be known to modern academics, exhibits particularly odd transcriptions of the names.

The dynasty of Lagash is well known through important monuments, and one of the first empires in recorded history was that of Eannatum of Lagash, who annexed practically all of Sumer, including Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Larsa, and reduced to tribute the city-state of Umma, arch-rival of Lagash. In addition, his realm extended to parts of Elam and along the Persian Gulf.

Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty, took Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. He is the last ethnically Sumerian king before the arrival of the Semitic named king, Sargon of Akkad.

Under Sargon, the Semitic Akkadian language came to the fore in inscriptions, although Sumerian did not disappear completely. The Sumerian language still appears on dedicatory statues and official seals of Sargon and his heirs. Thorkild Jacobsen has argued that there is little break in historical continuity between the pre and post Sargon periods, and that too much emphasis has been placed on the perception of a "Semitic vs. Sumerian" conflict (see Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture by T. Jacobsen). However, it is certain that Akkadian was also briefly imposed on neighboring parts of Elam that were conquered by Sargon.

Following the downfall of Akkadian Empire at the hands of barbarian Gutians, another native Sumerian ruler, Gudea of Lagash, rose to prominence, promoting artistic development and continuing the practice of the Sargonid kings' claims to divinity. Later on, the 3rd dynasty of Ur was the last great "Sumerian renaissance", but already the region was becoming more Semitic than Sumerian, with the influx of the waves of Amorites who were to found the Babylonian Empire.

|